Over the past two weeks, I have made an effort to bring more creativity into the way I approach the topic of assessment. One method I explored was a kind of improvisational “yes, and” approach to design derived from the acting practice of accepting what your scene partner has given you and then adding to it. I began with a key learning target from one of my previous designs, a course entitled, Excellence in Customer Service. In part of this course, emotional intelligence is highlighted as a key competency needed to connect with clients and deliver excellent customer service.

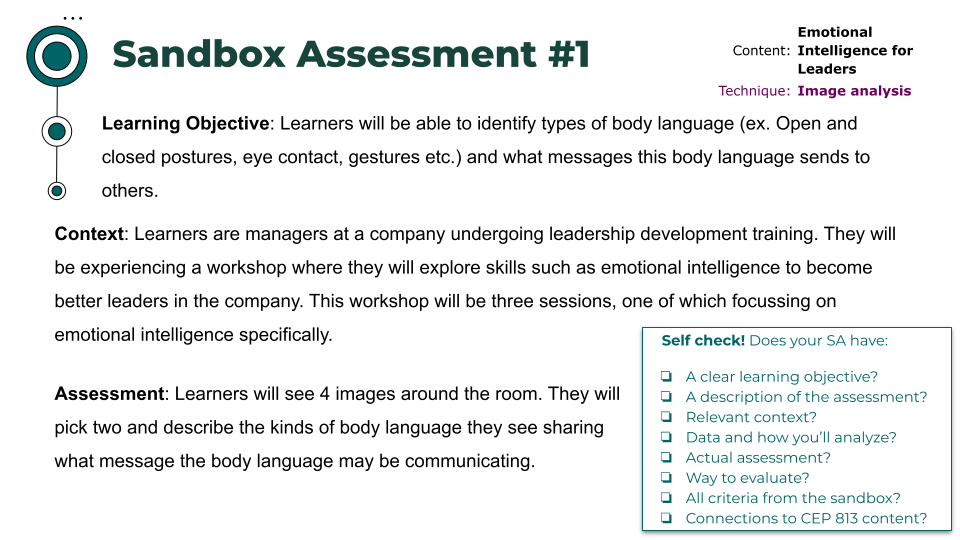

Once I had the learning target, I used a rotating set of randomly generated assessment techniques and structures, thanks to my colleagues in the MAET program. For one such iteration, I would be targeting emotional intelligence and assessing through an image analysis. This posed an engaging challenge: how could I create an ethical assessment that would hold up to scrutiny using only the information provided?

Typically, I start designing an assessment with the learning target and work backward, step by step, until I identify a clear path for how learners will be able to demonstrate their proficiency in the desired skill. Wiggins and McTighe (2005) posit that, “Backward design may be thought of […] as purposeful task analysis: Given a worthy task to be accomplished, how do we best get everyone equipped?” (p. 19). In this instance, however, I was being supplied with the “how” from the outset– what Wiggins and McTighe refer to as a content-focused design –leaving me to reconcile the alignment between my goals and the assessment method, rather than letting it emerge naturally through backward design. Below you will find a carousel of images that outline my notes during this first iteration, connecting the dots between the learners, their context, the assessment method, and data collection.

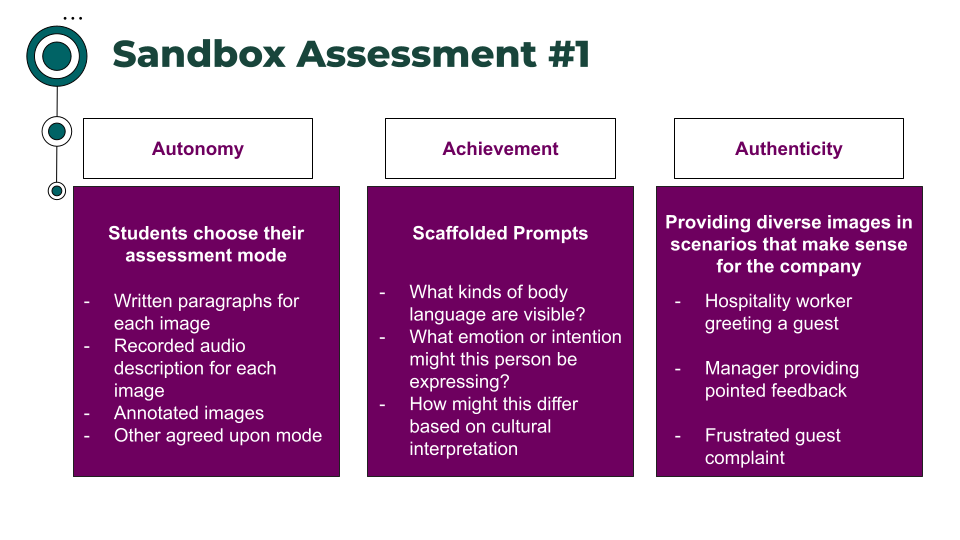

These creative constraints proved to be a surprisingly exciting way to generate ideas, despite the departure from my usual practice. They helped me avoid the judgment or perfectionism that often creeps into the design process– for better or for worse. Being randomly assigned an assessment method raised the question: could it still offer a feasible path to the learning objective? In order to give it a chance, I relied on my existing framework to pressure-test this assessment. If you are familiar with my work on learning and assessment, you will likely recognize these three pillars as the foundation for my designs:

- Is there authentic context?

- Is there autonomy for the learner?

- Is there achievement?

My framework guided this thought experiment and helped me evaluate the merits and shortcomings of each assessment method I sampled and pushed me to meet these standards despite the method provided to me.

Upon reflection, I have found that I can sometimes cut ideas off too quickly if I feel they will not serve the learner. For example, if an assessment method lacked validity and did not measure the intended learning objectives, I would not explore it further. Likewise, concerns surrounding fairness or objectivity could end an idea before it fully takes shape. The “yes, and” process provided a space to explore new ideas without fear of wasting time or falling short of an objective to see how they might measure up in the broader creative design. I have learned that variability is a welcome part of the drafting process.

Exploring the affordances of different assessment styles while checking it against my core principles fosters a more dynamic and intentional design. As I continue to iterate and experiment, I am reminded that creativity and structure do not have to be at odds. When guided by evidence-based principles, they can inform and strengthen one another.

Reference:

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design, (2nd Ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Leave a comment