For learners to engage effectively in language acquisition, it is essential that they feel safe enough to take risks. One key factor in fostering this sense of safety is Krashen’s (1982) affective filter hypothesis. The “affective filter” refers to emotional factors—such as motivation, anxiety, or self-concept—that influence language learning. A high affective filter, indicates that a learner’s state of mind is too emotionally fraught to engage meaningfully in language acquisition. Conversely, a low affective filter, suggests that a learner is in a more regulated emotional state, which facilitates deeper engagement with the learning process. In this paper, I will examine how principles of neuroscience and trauma-informed practices influence the affective filter through changes to cognitive load and input processing.

Language Learning in the Brain

When one learns something new, the brain processes information by taking in sensory input, encoding it into short-term memory, then with further processing, storing it in long-term memory, and retrieving it from long-term memory when needed (Growth Engineering, 2022). When learning a new language, there is a strong emphasis on input. Input in language learning references engaging with language through reading or listening that is at their level of proficiency or just beyond it. The complexity of input is important because the learner needs to interact with a defined scope of new information in order to encode it into a memory. If learners are exposed to a large amount of new information with limited scaffolds or preexisting knowledge, the brain is not able to transfer the input into memory. This is due to an unduly arduous cognitive load – the amount of energy the brain spends on working memory (Wikipedia, n.d.). When the cognitive load is too high, the brain will not store the sensory input into short-term memory and it never has a chance to get to long-term memory. High cognitive load can result in the learner feeling overwhelmed, lost, and anxious, raising the affective filter. Controlling how much information is being introduced beyond what the learner already is familiar with allows for a better chance of encoding for later retrieval of the information allowing for the affective filter to remain lower (Krashen, 1982).

Conditions for Learning in the Brain

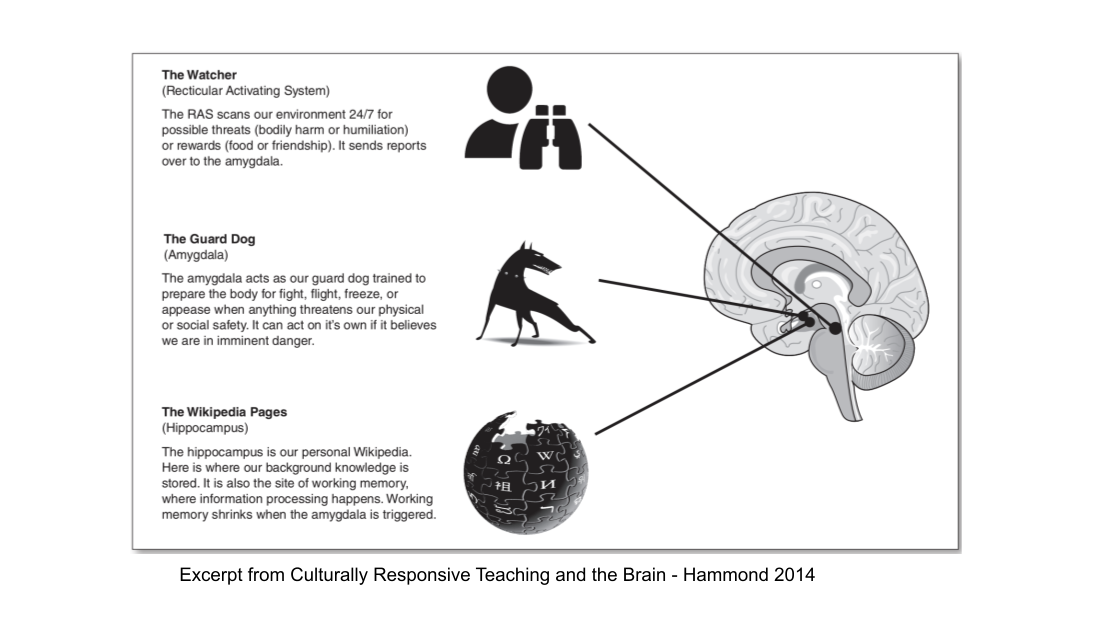

The complexity of learning increases when we consider each learner’s unique context, relationships, and responsibilities. Specifically, when the brain experiences stress, trauma, or anxiety, it is primarily operating from what can be called the reptilian brain, composed of the brainstem and cerebellum (Hammond, 2014). These areas are associated with our baseline functions like breathing and our heart pumping for the purpose of keeping our body alive, but are also known for their ability to react rather than think through situations (Hammond, 2014). Learning is not a priority during stressful times. Other parts of the brain are impacted by stress as well, specifically the limbic system. The limbic system houses the hippocampus, thalamus, and amygdala. The thalamus and hippocampus contribute to sensory and memory processing respectively and are required for learning. However, the amygdala takes over during stressful experiences and can bypass the regular channels in the limbic system that call for processing thoughts and emotions and instead go straight to the reptilian brain, often resulting in fight, flight, or freeze response instead. In these conditions, the brain cuts the learner off from being able to access information in their short-term or long-term memory. This high affective filter creates an impasse to encoding the input into the short-term memory (Hammond, 2014).

Implications of the Affective Filter for Language Learning Experiences

When designing for language learning, educators must consider the impact of the messages coming from the culture they foster with learners, the breadth and depth of content in each learning experience, and how and when feedback is being shared with students. Each learner’s threshold for cognitive load and emotional sensitivity to triggers vary and can have implications for whether learners will be able to engage with the learning process. It is therefore essential that learners feel affirmed and safe in the learning environment so they can take the risks necessary for learning language. Without a sense of safety, learners are less likely to engage with the language and may be pushed into a defensive state, increasing their affective filter, and preventing access to short-term memory processing, long-term memory, or higher-order thinking.

References:

Cognitive load. (2024, November 12). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_load

Growth Engineering. (2022, August 2). What is information processing theory? Growth Engineering blog. https://www.growthengineering.co.uk/information-processing-theory/

Hammond, Z. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin Press.

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice. Learning, 46(2), 327-69.

Leave a comment